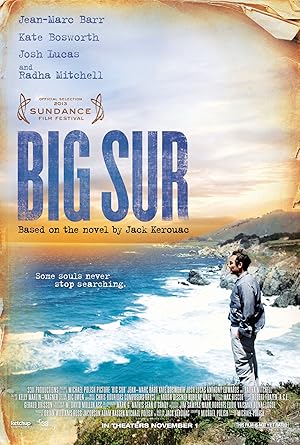

Big Sur

In the early 1950s, the nation

recognized in its midst

a social movement

called the Beat Generation.

A novel titled "On the Road"

became a best seller,

and its author, Jack Kerouac,

became a celebrity,

powerful and successful book,

but partly because

he, uh, seemed to be

the embodiment

of this new generation.

So here he is, Jack Kerouac.

3,000 miles from Long Island.

It's the first trip I've taken

away from my mother's house

since the publication

of "Road" three years ago.

All over America,

high school and college kids

thinking Jack Kerouac

is 26 years old

and on the road

all the time hitchhiking,

years old, bored and jaded.

The book that made me famous

and, in fact, so much so,

I've been driven mad

for three years

by endless telegrams,

phone calls, requests,

mail, visitors,

reporters, snoopers.

I was surrounded

and outnumbered...

and had to get away

to solitude again or die.

So Lawrence Ferlinghetti

wrote and said,

"Come to my cabin in Big Sur.

No one'll know. "

Although Lawrence and I

exchanged huge letters

outlining how I would sneak in

quietly into the West Coast,

I'd ruined my secret return to San

Francisco by getting silly drunk

and marching forth into North

Beach to see everybody.

Everyone recognized me.

I'm telling you.

Hey, everybody,

the bloody king of the

beatniks is back in town.

Two days of that,

including Sunday,

the day Lawrence Ferlinghetti

is supposed to pick me up

at my secret skid row hotel

and drive me to Big Sur woods.

One fast move,

or I'm gone.

You say I'm alone,

and the cabin is suddenly home

only because you made one meal

and washed

your first meal dishes.

Then nightfall.

The flies retreat

like polite

Emily Dickenson flies,

and when it's dark, they're

all asleep in the trees.

Maybe the bees got

a message to come and see me,

all 2,000 of 'em,

which seems to happen like

a big party once a week.

No booze, no drugs, no binges,

no bouts with beatniks

and drunks

and junkies and everybody.

...forehead.

No better.

What I do now next?

Chop wood?

Long nights simply thinking

about the usefulness

of that little wire scour,

those little

yellow copper things

you buy in supermarkets

for 10 cents,

all to me

infinitely more interesting

than the stupid and senseless

"Steppenwolf" novel

in the shack,

which I read with a shrug,

this old fart reflecting

on conformity of today,

and all the while, he thought

he was a big Nietzsche.

Because on the fourth day,

I began to get bored

and noted it in my diary

with amazement,

"Already bored?"

Even though the handsome

words of Emerson

would shake me out of that,

where he says in one of those

little red leather books

and is relieved and gay

when he has put

his heart into his work

and done his best.

Yet I went crazy

inside three weeks.

In me and in everyone,

I felt completely nude of all

poor protective devices,

like thoughts about life

or meditations under trees

and the ultimate

and all that sh*t.

In fact, the other pitiful

devices of making supper

or saying, "What I do

now next? Chop wood?"

I see myself as just doomed,

an awful realization that I have

been fooling myself all my life

thinking there was a next thing

to do to keep the show going,

and actually

I'm just a sick clown,

not even really

any kind of common sense,

animate effort to ease the soul

in this horrible, sinister

condition of mortal hopelessness.

I hate to write.

All my tricks laid bare,

even the realization

that they're laid bare itself

laid bare is a lot of bunk.

The sea seems to yell to me,

"Go to your desire.

Don't hang around here.

"Why not live for fun

and joy and love

"or some sort of girl

by a fireside?

Why not go to your desire

and laugh?"

But I ran away

from that seashore

and never came back again

without that secret knowledge

that it didn't want me there,

that I was a fool to sit there

in the first place.

The sea has its waves.

The man has

his fireside, period.

It's time to leave.

I'm so scared by that

iodine blast by the sea

and by the boredom

of the cabin.

I'm tired of my food,

forgot to bring Jell-O.

You need Jell-O after all that bacon

fat and cornmeal in the woods.

Every woodsman needs Jell-O

or Cokes or something.

But before I go, I realize

this isn't my own cabin.

Here's the second signpost

of my madness.

I have no right to hide

Ferlinghetti's rat poison

as I'd been doing,

feeding the mouse instead,

so like a dutiful guest

in another man's cabin,

I take the cover

off the rat poison,

but compromise by simply leaving

the box on the top shelf.

I go dancing off like a fool

from my sweet retreat,

rucksack on back,

after only three weeks

and really after only

three or four days of boredom

and go hankering back

for the city.

I figure I'll get a ride

to Monterey real easy

and take the bus there

and be in Frisco by nightfall

for a big ball of wino yelling

with the gang.

I feel, in fact, Lew Welch

ought to be back by now,

or Neal Cassady

will be ready for a ball,

and there'll be girls

and such and such,

forgetting entirely

that only three weeks previous,

I'd been sent fleeing

from that city by the horrors.

This is the first time

I've hitchhiked in years,

and soon I begin to see that

things have changed in America.

You can't get a ride

anymore, but, of course,

especially on a strictly

tourist road like this

or coast highway

with no trucks or business.

But the tourists,

bless their hearts,

after all, they couldn't know,

happy hike with my rucksack,

and they drive on.

If you should ever

stop using that smile,

how could the world go on?

We were gonna come down

to see you this weekend.

You should have waited.

Your mom wrote.

She said your cat died.

I'll go get the letter.

My relationship with my cats

has always been dotty.

Some kind of psychological

identification of the cats

with my dead brother Gerard,

who taught me to love cats

when I was three and four

and we used to lie

on the floor on our bellies,

then watch them lap up milk.

The death of a cat

means little to most men,

but to me, it was exactly...

and no lie and sincerely...

like the death

of my little brother.

What the hell?

Why bother grown-up men

and poets at that

with your own troubles?

Maybe you should

go back to the cabin

for a couple of weeks, huh?

Or are you just

gonna get drunk again?

I'm gonna get drunk, yes.

You can go back soon, huh?

Okay, Lorry.

Did you write anything?

We can drink to that.

It's still a cat.

I know he meant a lot to you.

You know that's

the way of things.

Hey, so by City Lights

bookstore the other day,

there was a workman out

in the front, you know,

hammering away with a

jackhammer really loud.

"Yahh. "

Right in the street.

And the psychic above the

studio leans out the window,

and he says,

"When are you gonna stop

Translation

Translate and read this script in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this screenplay to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Big Sur" Scripts.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 3 Mar. 2025. <https://www.scripts.com/script/big_sur_4071>.

Discuss this script with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In