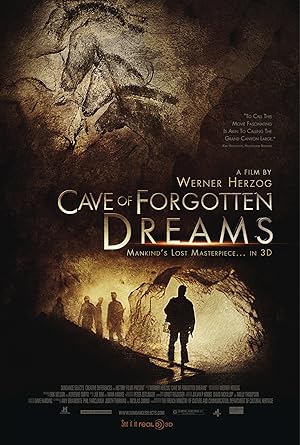

Cave of Forgotten Dreams

This is

the Ardche River

in southern France.

Less than a quarter of a mile

from here,

three explorers set out

a few days before Christmas

in 1994.

They came along this way.

They were seeking drafts of air

emanating from the ground,

which would point

to the presence of caves.

Eventually, they sensed

a subtle airflow

and began clearing away rocks,

revealing a narrow shaft

into the cliff.

It was so narrow

that a person could barely

squeeze through it.

They descended

into the unknown.

They were about to make

one of the greatest discoveries

in the history

of human culture.

At first,

the cave did not appear

to contain anything special,

aside from being

particularly beautiful.

But then deep inside,

they found this.

It would turn out

that this cave was pristine.

It had been perfectly sealed

for tens of thousands of years.

It contained by far

the oldest cave paintings,

dating back

some 32,000 years.

In fact, they are the oldest

paintings ever discovered,

more than twice as old

as any other.

In honor of its leading

discoverer, Jean-Marie Chauvet,

the cave now bears the name

Chauvet Cave.

This is the road

in the Ardche Gorge

leading to the cave.

It is early spring.

We have been given

an unprecedented endorsement

by the French

Ministry of Culture

to film inside the cave.

From the first day

of its discovery,

the importance of the cave

was immediately recognized,

and access was shut off

categorically.

Only a small group of

scientists is allowed to enter.

They are archaeologists,

art historians,

paleontologists,

and geologists, among others.

They are here to perform

their studies together

during a few short weeks

at the end of March

and the beginning of April.

This is one of the rare times

anyone, with the exception

of two guards,

is allowed inside the cave.

The cave is like a frozen flash

of a moment in time.

The reason

for its pristine condition

is this rock face.

Some 20,000 years ago,

it came tumbling down

in a massive rock slide,

sealing off the original

entrance to the cave

and creating

a perfect time capsule.

A wooden walkway leads to

the entrance of Chauvet Cave.

The narrow tunnel through which

the discoverers crawled

has been widened

and locked

with a massive steel door

like a bank vault.

Once we pass through this door,

it will be locked behind us

so as not to compromise

the delicate climate inside.

For this, our first exploration

into the cave,

we are using a tiny,

nonprofessional camera rig.

In this first narrow

holding room,

we are fitted

with sterile boots

and given safety instructions.

We have this, okay.

Once you've set this

on the rope,

you don't touch it.

Jean Clottes

was the first scientist

to inspect the cave

a few days after its discovery.

For five years,

until his retirement,

he served as head

of the scientific team.

Our guide leads us

down a first sloping tunnel,

which ends in a vertical drop

to the cave floor.

Since our film crew

has been limited

to a maximum of four,

we must all perform

technical tasks.

In addition,

our time in the cave

has been severely restricted.

And I will take one light

as well.

So it's five past 3:00.

We have one hour.

Apart from time constrictions,

we are not allowed

to touch anything in the cave

or ever step off

the two-foot-wide walkway.

We can use only three

flat cold light panels

powered by battery belts.

- You see how,

when they made the passageways,

they protected

the stalagmites.

It's a nice touch.

Inevitably,

moving along in single file,

the film crew

will have no hiding places

to get out of the shot.

The first large chamber

we come to

is the original entrance

to the cave.

In prehistoric times,

before the rock slide,

daylight must have

illuminated this.

- So on the left

when we arrived inside the cave,

you can see the entrance,

and that was

the archaeological entrance.

People came

into the cave level,

not like us, down a ladder.

And then the cliff collapsed.

And then we've got the rubble

from the cliff.

From outside,

you cannot see it.

From inside, you can.

Over there, you've got the dots,

the red dots.

Those are the red dots

which I saw first

when I came into the cave,

big dots made with the palm

of the hand.

Well, here we have... - we have

a big cave bear skull, right?

Male, probably.

And you'll see many others.

You see, in this big chamber,

which is a really huge... -

it's the biggest in the cave... -

there are no paintings

except right at the end.

So this is probably relevant,

because when the entrance

was still open,

there must have been

some light here.

So they put the paintings,

really, in the complete dark.

See here.

This is a cave bear

painted in black.

The paintings

looked so fresh

that there were initial doubts

about their authenticity,

but this picture has a layer

of calcite and concretions

over it

that take thousands of years

to grow.

This was the first proof

that it was not a forgery.

- A beautiful horse here,

one of the most beautiful

in the cave.

And what is touching

is that it looks as if

it had been done yesterday.

Look how fresh it looks

with that technique.

And here we have,

behind the horse,

there are two mammoths,

big mammoths.

And here you can see

cave bear scratches,

and the cave bear scratches

are not the same color.

They look like

they might have been made

We are coming here to one of

the great spots of the cave,

which is the famous panel

of the horses.

It is of the... - one of the size

of a small recess.

And this small hole there

is where water comes out,

gurgling,

after there's been

something like a week of rain.

And that probably explains

why all those animals

were painted around that hole.

It's one of the great works

of art in the world.

For these Paleolithic painters,

the play of light and shadows

from their torches

could possibly have looked

something like this.

For them, the animals perhaps

appeared moving, living.

We should note that the artists

painted this bison

with eight legs,

suggesting movement,

almost a form of proto-cinema.

The walls themselves

are not flat

but have their own

three-dimensional dynamic,

their own movement, which was

utilized by the artists.

In the upper left corner,

another multilegged animal.

And the rhino to the right

seems also to have

the illusion of movement,

like frames

in an animated film.

The painters of the cave

seem to speak to us

from a familiar

yet distant universe.

But what we are seeing here

is part of millions

of spatial points.

Today scientists have mapped

every single millimeter

of the cave

using laser scanners.

in the cave is known.

This is the shape of the cave

in its entirety.

From end to end,

it is about 1,300 feet long.

This map is the basis

for all scientific projects

being done here.

- We are working to create

new understanding of the cave

Translation

Translate and read this script in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this screenplay to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Cave of Forgotten Dreams" Scripts.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 3 Mar. 2025. <https://www.scripts.com/script/cave_of_forgotten_dreams_5222>.

Discuss this script with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In