Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy? Page #11

because we assumed she'd have

to take care of the children.

She'd need a job.

And the kids kind of grew

up in this atmosphere,

but I don't think they felt

any particular tension.

My wife told me once

that my probably eight...,

ten-year-old daughter, I guess,

told her when she came

home from school...

She asked, "What did you

do in show-and-tell?"

She said, "Well, I described...

I told them how my

father was in jail."

What makes you happy?

Happy?

Children, grandchildren,

friends, you know.

I don't really think about it much.

I don't spend much... anytime

in self-indulgence.

Especially since my wife

died, I do almost nothing.

You know, don't go the movies, don't

go to the theater. I don't eat out.

I do what I have to do.

But, I mean, there

are a lot of things

that are very gratifying,

so, for example...

especially seeing victims.

Like, I just came back from

Turkey, where I was...

I've been there several times.

It's always issues

related to the

repression of the Kurds.

Actually, I was there...

the first time I was there

was to take part in a trial

and be a codefendant.

But this time, it was for a

conference on repression

and freedom of expression.

You see people who are

really dedicated, courageous,

struggling all the time,

standing up against repression.

It's quite inspiring.

A couple of months before that,

I was in southern Colombia.

Colombia has the worst

human rights record

in the hemisphere

and, of course,

the most US. military aid

in the hemisphere.

They correlate.

In these places,

I was visiting quite remote

endangered villages,

and the people were just inspiring.

It actually was a very moving

experience, personally.

I was there in part because

they were dedicating a forest

to the memory of my wife.

And it's the kind of

compassion and kindness

that you just don't see

in the world we live in.

And it was just kind of natural,

no pretentiousness

about it, ceremony.

And you see things like that

all over the world here too,

not much in the circles in

which we live, you know,

mainly in intellectual

circles and elsewhere.

Much more abstract, even,

than in the case of the tree.

There was a sudden explosion...

Answers to, like the phonetics,

I don't care about.

My father worked on history

of the Semitic languages...

During the earlier exposure,

where the child is not...

We learn that children

know quite a lot...

It's a story about a donkey

named Sylvester...

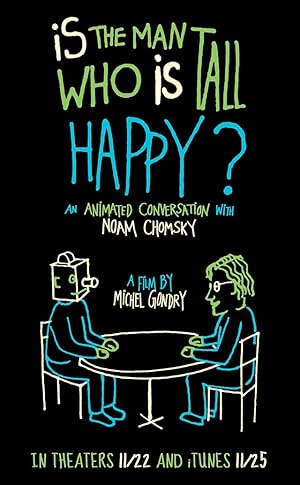

In one of your books from the '70s,

you give this example

of the sentence,

"The man who is tall

is in the room,"

and how the child naturally

can postulate the question.

And I was wondering

if you could explain just quickly, because I

could do a very nice animation from that.

There's a simple question, and it's

interesting that it never bothered anyone.

It's a little bit like,

for 2,000 years,

scientists were satisfied

with simple explanation

for an obvious fact.

If you take an apple

and you detach it from a tree,

it's going to go down.

If you take steam,

it's going to go up.

So 2,000 years, the answer was,

"Well, they're going

to their natural place.

End of discussion."

As soon as people started

getting puzzled about that,

like Galileo and Newton,

then you have modern science.

- But can you...

- This is the same.

Take the sentence that you gave me,

"The man who is tall is happy,"

or whatever it is.

If you want to form a question

from that,

you take the word "is,"

and you put it in the front.

So, "Is the man who is tall happy?"

Right? That's the question.

You don't take

the first occurrence of "is."

You don't take the closest one

to the front...

and say, "Is the man

who tall is happy?"

That's gibberish.

How does it... why?

I mean, why doesn't the child

do the simple thing,

take the first occurrence of "is"

and put it in front?

That's... computationally,

that's much easier

than finding the main occurrence,

which requires knowing

the phrases and so on.

But it's an inconceivable error.

No child has ever made that error.

And it's the same in all...

You know, with minor variations,

the same principle holds

in all languages, so why?

Well, you know, there are

some interesting explanations

for why, but this is a good example

of the brute force approach.

In computational cognitive science,

where they,

as a matter of principle,

want to believe that the mind

is essentially empty...

The man who is tall is happy.

The man who is tall is happy.

The man who is tall is happy.

Then Noam took my pen

and wrote the following sentence.

Look, there are

serious questions about it.

Like, take, "The man who is tall

is happy."

This is the predicate,

this is the subject, okay,

and this is sort of

the main element.

You know, that's the main element

of the whole sentence,

and that's the one

that structurally is closest to

the middle, to the beginning.

This one is more remote from

the beginning structurally,

because you have to work through

this whole business, okay?

So structurally speaking,

this is the closest to the front.

Linearly, this is the closest

to the front.

Now, the question is,

"Why do you use

structural proximity and

not linear proximity?"

And it's not just this case;

it's everything...

every language, every construction.

Is that evidence of this

generative grammar?

Well, that's the data, and

there is a principle.

I mean, the principle is, "Keep

to minimal structural distance."

Okay, now, where

does that come from?

This part is probably

just a law of nature.

Computation tries to do

things in the simplest way,

but the structural distance

part is a fact about language.

I mean, you could have

minimal computation

if you did it this way.

In that case, what we would say:

"Is the man who tall is happy?"

The child picks

structural closeness

because that's a

property of language,

probably genetically determined.

Yeah, but that's about

all there is to it.

The man who is tall is happy.

Yes, the man who is

tall is very happy.

Is the man tall is happy?

Is the man who is tall happy?

Is the man who is tall happy?

Is the man who is tall is happy?

Is the man who is tall happy?

Is the man who tall is happy?

I guess we've been...

Okay.

We got to rush him over.

He's going to miss the thing.

Okay.

- Good to see you again.

- Yeah.

I'm glad you're doing well.

We got to get you out of here.

Your bags...

Translation

Translate and read this script in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this screenplay to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?" Scripts.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 24 Dec. 2024. <https://www.scripts.com/script/is_the_man_who_is_tall_happy_10984>.

Discuss this script with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In