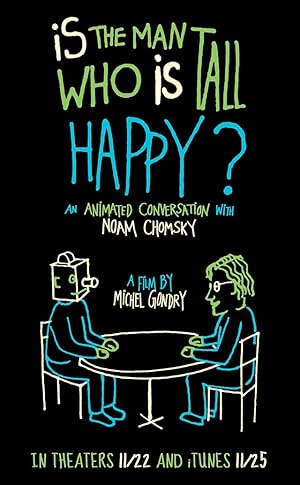

Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy? Page #8

So it's understandable

that there should be

one or another form

of religious belief.

I think we should change

the camera.

I think it's time for the break.

- Lunch break.

- Oh, I see, okay.

So we get another camera next time?

Yeah, I'm going to use

this one, because I...

Okay.

The discussion is so good,

I don't want to lose a drop.

In fact, I eventually decided

to stick to my plan

and continue to shoot

the rest of the interview

with my old mechanical Bolex.

This way, I could only film

short fragments of Noam,

and I was committed

to what moments he would appear

in the final version.

I was also committed

to have to animate 98%

of the whole film

and hear the sound

of my cranky camera

each time Noam would appear

so I would have to illustrate

Do you remember

what was your first

thinking of linguistics?

There's background.

Like, when I was a child,

my father worked on history

of the Semitic languages,

so I read work of his.

Like, I read

his doctoral dissertation

when I was... I don't know...

10,12 years old.

It was on a medieval grammarian,

medieval Hebrew grammarian,

so I kind of knew... had some

acquaintance with the field.

Later I sort of got into it

by accident.

And when I got into it,

I found it intriguing, but...

and did things

that we were taught to do.

And at some point, I realized,

"This doesn't make any sense."

You know, the way

we're taught to do things

was descriptivist.

So the way you...

linguistics at that time

and, to a large extent, still

is a matter of organizing data.

So a typical assignment

when I was an undergraduate,

let's say, would be to take data

from some American Indian language

and put it into an organized form.

You didn't ask the question,

"Why is the data this way

and not some other way?"

That wasn't a question

that was asked.

In fact, I remember, dramatically,

the first talk I gave

when I was a graduate student

invited to a major university

to give a talk

on work that I was doing,

the normal thing.

The leading figure

in the department,

one of the famous linguists,

met me at the airport,

and, you know,

we drove to the college,

and on the way, we talked,

and I asked him

what he was working on.

And he said

he's not doing any work now.

What he's doing is just

collecting data and storing it,

and he had a good reason,

which is implicit

in the linguistics of that day

in Europe and the United States.

Computers were coming along,

so pretty soon,

you'd be able to analyze

huge masses of data.

It was assumed that the procedure,

the methods of analysis

that had been reached

in the structuralist traditions,

that they were the right way

to understand everything

about language.

Well, you know, if you

sharpened up those procedures,

you could program it

for a computer.

Then you feed the data in,

and you're done.

How old were you?

- That was 1953.

- Okay.

So, I mean, I kind

of half believed it,

because that's the way

I was trained,

but the other half of my brain

was telling me,

"This makes absolutely no sense."

Can you tell me the transition

and also the inspiration

that started your theory?

It was pretty straightforward.

When I was an undergraduate,

I had to get an honors thesis.

You do a piece of work

that's your honors thesis.

And the faculty member

who I was working with...

very famous and very

significant person,

very influential, rightly...

he suggested to me

that I do a structural analysis

of modern Hebrew.

Well, I knew some Hebrew,

so it made sense,

and I did what we

were supposed to do.

What you're supposed to do

is get an informant

and then carry out

field work procedures.

So there's a set of routines

you go through

to take the data

from the informant, you know,

find the phonology,

find the morphology, you know,

a few comments about

syntactic structure,

comments about the semantics,

and that's your thesis.

So I started going through

the routine with him.

And after about a month,

I realized,

"This is totally ridiculous."

I mean, I know the answers

to these questions.

Why am I asking him?

And the questions that I don't

know the answers to,

like the phonetics,

I don't care about.

But the parts that I care about,

I already basically know

the answers,

so what do I care?

Why do I have to get it from him?

So I stopped the informant work,

and I just started doing

what seemed like

the obvious thing to do:

write a generative grammar.

And that's what I did,

but it was kind of a hobby.

I don't think

anyone even looked at it.

You know, in fact,

it finally was published

about 30 years later, I think.

Can you tell me,

like, in a simple way,

like, this first approach

of generative grammar?

It's almost a truism.

I mean, if you think

about what a language is,

say, what you and I know,

we have somehow in our heads

a procedure for constructing

an infinite array

of structured expressions,

each of which is assigned a sound

and assigned

a semantic interpretation.

This is like a truism.

Furthermore,

these structured expressions

have the property of

what's called digital infinity.

They're like the numbers,

the natural numbers.

You know, there's five and six

but nothing in between.

That's not natural numbers anymore.

And the same with language.

There's a five-word sentence,

a six-word sentence.

There's no 51/2 word sentence.

They're very much unlike, say,

the communication system of bees

or any other system, you know.

Now, that's very rare

in the natural world,

digital infinity.

And by that time, say, late '40s,

the mathematics of it

were well understood.

The theory of computation

had been developed,

theory of recursive functions.

So these were familiar concepts

within contemporary mathematics,

and, you know, I studied them

when I studied advanced logic

and mathematics.

And it just sort of fell together.

The... you have this system

of digital infinity.

It's a procedure of some sort

that generates an infinity

of structured expressions.

That's a generative grammar,

in fact; that's all it is.

So that ought to be

the core of the study.

And then comes the question,

"Well, okay, what is it?"

Then you run into the problem

I mentioned before.

As soon as you try to do it,

you find

that in order to deal

with the data available,

it has to be extremely complex

and intricate.

But that doesn't make any sense

either,

because every child masters it

in no time,

so somehow it can't be rich

and complex.

And then comes the field.

The field is to try to show

that what appears to be

rich and complex

is, at the core, just very simple.

Actually, you know,

when you think about it,

as we started to do from the '50s,

there's an evolutionary basis

for this too.

Language is a very

curious phenomenon.

I mean, one question

two questions is, "Why are there

any languages at all?"

And another one is,

Translation

Translate and read this script in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this screenplay to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?" Scripts.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 23 Feb. 2025. <https://www.scripts.com/script/is_the_man_who_is_tall_happy_10984>.

Discuss this script with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In