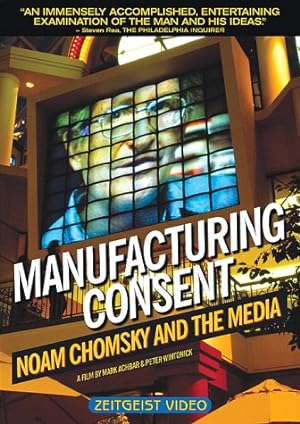

Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media Page #6

- NOT RATED

- Year:

- 1992

- 167 min

- 1,931 Views

So what you have is institutions, corporations -

big corporations -

that are selling relatively privileged audiences

to other businesses.

Well, what point of view

would you expect to come out of this?

Without any further assumptions,

what you'd predict is

that what comes out is a picture of the world,

a perception of the world,

that satisfies the needs,

and the interests, and the perceptions

of the sellers, the buyers, and the product.

Now, there are many other factors

that press in the same direction.

If people try to enter the system

who don't have that point of view,

they're likely to be excluded

somewhere along the way.

Ater all, no institution is going to

happily design a mechanism to self-destruct.

That's not the way institutions function,

so they all work to exclude, or marginalise,

or eliminate dissenting voices,

or alternative perspectives and so on

because they're dysfunctional.

They're dysfunctional to the institution itself.

Do you think you've escaped

the ideological indoctrination

of the media and society that you grew up in?

Have I? Oten not.

I mean, when I look back,

and think of the things that I haven't done

that I should have done, it's...

it's very...

it's...

not a pleasant experience.

So, what's the story

of young Noam in the school yard?

Yeah, another...

I mean, that was a personal thing for me.

I don't know why it should interest anyone else,

but I do remember...

- You drew certain conclusions.

- It had a big influence on me.

I remember when I was about six, I guess,

first grade, there was the standard fat kid

who everybody made fun of,

and I remember in the school yard,

he was on a...

you know, standing right outside

the school classroom,

and a bunch of kids outside sort of taunting him,

and... you know, and so on,

and one of the kids actually brought over

his older brother

from third grade instead of first grade.

Big kid.

And he was going to beat him up or something,

and I remember going up to stand next to him,

feeling somebody ought to... help him,

and I did for a while, and then I got scared,

and I went away,

and I was very much ashamed of it aterwards,

and sort of felt, you know...

"I'm not going to do that again."

That's a feeling that's stuck with me -

you should stick with the underdog.

And the shame remained.

I should have stayed there.

You were already established, you were a

professor at MIT, you'd made a reputation,

you had a terrific career ahead of you.

You decided to become a political activist.

Now, here is a classic case of somebody the

institution does not seem to have filtered out.

I mean, you were a good boy up until then,

were you?

Or you'd always been a slight rebel?

Pretty much. I had been pretty much outside.

You felt isolated and out of

sympathy with the currents of American life,

but a lot of people do that.

Suddenly, in 1964,

you decide, "I have to do something about this".

What made you do that?

That was a very conscious,

and a very uncomfortable, decision,

because I knew

what the consequences would be.

I was in a very favourable position.

I had the kind of work I liked,

we had a lively, exciting department,

the field was going well, personal life was fine,

I was living in a nice place, children growing up.

Everything looked perfect,

and I knew I was giving it up,

and at that time, remember,

it was not just giving talks.

I became involved right away in resistance,

and I expected to spend years in jail,

and came very close to it.

In fact,

my wife went back to graduate school in part

as we assumed

she would have to support the children.

These were the expectations.

And I recognised

that if I returned to these interests

which were the dominant interests

of my own youth,

life would become very uncomfortable.

Because I know that in the United States

you don't get sent to psychiatric prison,

and they don't send a death squad ater you

and so on,

but there are definite penalties

for breaking the rules.

So these were real decisions,

and it simply seemed at that point

that it was just hopelessly immoral not to.

I'm Noam Chomsky, I'm on the faculty at MIT,

and I've been getting

more and more heavily involved

in anti-war activities for the last few years.

Beginning with writing articles,

and making speeches,

speaking to congressmen

and that sort of thing,

and gradually getting involved more and more

directly in resistance activities of various sorts.

I've come to the feeling myself

that the most effective form of political action

that is open to a responsible

and concerned citizen at the moment

is action that really involves direct resistance,

refusal to take part in

what I think are war crimes,

of American aggression overseas

through non-participation, and support

for those who are refusing to take part,

in particular,

drat resistance throughout the country.

I think that we can see quite clearly

some very, very serious defects and flaws

in our society,

our level of culture, our institutions

which are going to have to be corrected

by operating outside of the framework

that is commonly accepted.

I think we're going to have to

find new ways of political action.

I rejoice in your disposition

to argue the Vietnam question,

especially when I recognise

what an act of self-control this must involve.

It really does.

- You're doing very well.

- You're doing very well.

- I lose my temper. Maybe not tonight.

Maybe not tonight...

because if you would

I'd smash you in the goddamn face.

That's a good reason for not losing your temper.

You say, "The war is simply an obscenity,

a depraved act by weak and miserable men."

Including all of us.

Including myself. That's the next sentence.

Oh, sure, sure, sure.

Because you count everybody

in the company of the guilty.

- I think that's true in this case.

- It's a theological observation.

No, I don't think so.

If everybody's guilty of everything,

then nobody's guilty of anything.

No, I don't believe that.

I think the point that I'm trying to make,

and I think ought to be made,

is that the real...

at least to me -

I say this elsewhere in the book -

what seems to me a very, in a sense, terrifying

aspect of our society and other societies

is the equanimity and the detachment

with which sane, reasonable, sensible people

can observe such events.

I think that's more terrifying than

the occasional Hitler or LeMay that crops up.

These people would not be able

to operate were it not for the...

this apathy and equanimity,

and therefore I think that it's in some sense

the sane, and reasonable, and tolerant people

who share a very serious burden of guilt

that they very easily

throw on the shoulders of others

who seem more extreme and more violent.

New York City's so-called Canyon of Heroes.

Americans were officially welcoming

the troops home from the Persian Gulf war.

It worked out really great for us.

Translation

Translate and read this script in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this screenplay to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Manufacturing Consent: Noam Chomsky and the Media" Scripts.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 23 Feb. 2025. <https://www.scripts.com/script/manufacturing_consent:_noam_chomsky_and_the_media_13340>.

Discuss this script with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In