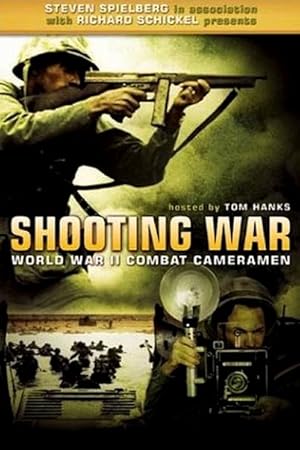

Shooting War

- Year:

- 2000

- 88 min

- 21 Views

Other wars had been photographed.

World War II was covered

from start to finish

in every service, in every theatre.

For the first time,

civilians knew something

of how their sons, husbands

and brothers lived and died

in this vast crucible.

The images of this war

burned our eyes and spirits

and welded us together.

I loved it because it was dangerous.

I'm a fraidy-cat,

but if there was a job to do, I did it.

No matter how horrible the action was

that you were covering,

when you looked through,

that glass was your filter.

I got carried away one time

and got out in front of the gun,

shooting the gun firing.

That was a big mistake.

The muzzle blast knocked me 40 feet,

ass over teakettle.

We hit an intersection

where we were shot at.

into the cab of the truck.

When you're baling out of that aeroplane,

on the way down, you say, "Oh, no."

But shells, you can't say anything.

"Stop. I'm here."

Those are men who took the pictures

by which we remember World War II.

Some of their images are immortal.

Many have been hidden

in the archives for decades.

Whether their pictures

are famous or not,

what you are about to see is unique:

War stories backed by the irrefutable

evidence of the films they made.

In their hands, the camera became

a weapon more potent than the rifle,

a weapon whose impact resonates

even more powerfully now,

as memory is transformed into history.

In 1941, we were as unprepared

to photograph war as to wage it.

When John Ford made his film

on Pearl Harbor,

the Japanese attack was recreated,

intercut with old newsreel footage

and a few feet of the real thing.

Men, man your battle stations.

God bless you.

Hollywood cameraman Gregg Toland

re-staged these scenes

The actors are obviously amateurs,

but they are real sailors.

The planes were the contribution

of 20th Century Fox special effects.

In this out-take, you can see the wires

supporting the model Zero.

Ford organised his photographic branch

before the war, as part of the OSS.

Toland's crew set fire to crashed planes,

adding drama to his footage,

but his feature-length parable

about American unpreparedness

was judged unreleasable.

Ford now took a more active hand,

cutting December 7th to 34 minutes.

He retained much of the miniature

footage, also made at Fox.

This material, never before seen,

was shot in colour,

though the film was released

in black and white.

This is Hollywood's version

of Pearl Harbor's battleship row

and the Ford-Toland version

of the attack on it.

There was authentic footage

of the Nevada trying to escape,

but Ford preferred this reconstruction.

It matched the rest

of his fake footage better.

His goal was not strict authenticity.

He was out to stir the nation.

There was enough reality to win an

Academy Award for best short subject.

As Toland and Ford worked

America mounted its first

aggressive response to Pearl Harbor:

A navy task force

under Admiral "Bull" Halsey.

It carried James Doolittle's flyers

and 16 B-25s aboard the Hornet.

Hal Kempe was

a photographer's mate on the ship.

I've heard many stories. Some say

we slipped out under cover of darkness.

We went under

the Golden Gate Bridge at noon.

We had the planes

lined up on the flight deck.

It looked like it was a ferry trip.

After we were at sea

they re-spotted the flight deck.

They took each B-25,

and placed them with their tails

extending out over the edge.

They put one on each

port and starboard side

until the lead plane had

sufficient run for his take-off.

That was one third

the normal take-off distance.

The raiders were spotted

by Japanese picket boats.

They were sunk but might

have radioed a warning.

There was no choice

but to launch the attack.

So they said, "Man your planes.

We're gonna launch."

So we were launching

eight hours too soon.

Doolittle was first.

He went and the rest

of the crews were wondering,

"Can it be done?"

The raiders, volunteers, had practised

short-run take-offs on land,

a few from a carrier deck,

but never in bad weather.

Yet all were safely launched

for their 30 seconds over Tokyo.

Halsey's concern: The early launch

made it impossible

to make safe landings in China.

Yet all but three flyers survived the raid.

It did little damage,

except to enemy morale.

They carried four 500lb bombs each.

That's not very much,

when you really look at it,

but enough to put the fear

of God into them for a while.

The Doolittle raid provoked

a Japanese counter-attack

aimed at destroying the US Pacific fleet.

But we had broken their code and

knew they would attack Midway Island.

This evened the odds for the carriers

as they approached

the war's first great naval battle.

Midway was a pair of tiny coral atolls

vital to the defence of Hawaii.

This time, John Ford

was present with a film crew.

Ford himself operated a camera and

was wounded getting these pictures.

for the film he fashioned.

The crucial battle was at sea between

ships that never saw one another.

They didn't know exactly

where the Japanese fleet was,

but the torpedo-squadron skipper had

an idea it was in a certain direction.

He went off there.

He ran into the whole bunch of 'em.

And 15 or 16 torpedo planes went down.

These men of torpedo squadron eight

found the Japanese carriers.

They scored no hits,

but they distracted enemy gunners,

allowing our dive bombers

to sink four carriers.

Only one man, George Gay,

on the right, survived.

One of Ford's crew shot these pictures.

The director made them into a short

memorial film for the next of kin.

Midway shifted the balance

of naval power in the Pacific.

It cost the Japanese

almost half their carriers.

continued to pose a deadly threat.

October, 1942. The Hornet steams

toward the battle of Santa Cruz

near Guadalcanal.

With the Enterprise, she was soon

fighting off assaults from the air.

How close the combat often was

is demonstrated by this sequence,

shot from the Enterprise.

A near miss shakes the Enterprise.

An enemy shadow is cast

on the flight deck as the ship fights on.

The camera catches the wild swing of

the huge ship as it takes evasive action.

But still the bombs rained down.

but not the cameraman.

The Hornet did not survive either.

We were listing to the starboard.

Real heavy list.

I went to the fantail

to help with the wounded,

where I stayed until

we finally abandoned ship.

I swam out about 45 degrees this way.

Got out so far

and here come the destroyers.

I figured, "This is gonna be

a piece of cake. Pick us up real quick."

Then they backed down and took off.

around the ship and firing.

"What are they firing at?"

We looked in the sky.

Translation

Translate and read this script in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this screenplay to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Shooting War" Scripts.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 21 Feb. 2025. <https://www.scripts.com/script/shooting_war_18036>.

Discuss this script with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In