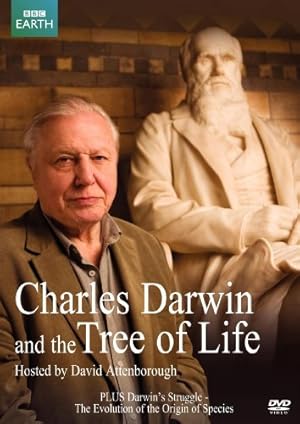

Charles Darwin and the Tree of Life Page #2

- Year:

- 2009

- 59 min

- 8,120 Views

He noted that most, if not all, animals

produce many more young

than live to breed themselves.

This female blue tit, for example,

may well lay a dozen eggs a year,

perhaps 50 or so in her lifetime.

Yet only two of her chicks need to

survive and breed themselves

to maintain the numbers

of the blue tit population.

Those survivors, of course,

are likely to be the healthiest

and best-suited

to their particular environment.

Their characteristics

are then inherited

so perhaps over many generations,

and particularly if there are

environmental changes,

species may well change.

Only the fittest survive.

And that was the key.

He called the process natural selection.

(BIRDSONG)

That would explain the differences

that he had noted in the finches

that he had brought back

from the Galapagos.

They were very similar

except for their beaks.

This one has a very thin, delicate beak,

which it uses to catch insects.

This one, on the other hand,

which came from an environment

where there were a lot of nuts,

has a big, heavy beak,

which enables it to crack them.

So maybe, over the vastness

of geological time,

and particularly if species were

invading new environments,

to very radical changes indeed.

Darwin drew a sketch in one

of his notebooks to illustrate his idea,

showing how a single ancestral species

might give rise

to several different ones,

and then wrote above it a tentative,

"I think".

Now he had to prove his theory.

abundant and convincing evidence.

He was an extraordinary letter writer.

He wrote as many as a dozen

letters a day

to scientists and naturalists

all over the world.

He also realised that when people had

first started domesticating animals

they had been doing experiments for him

for centuries.

All domestic dogs are descended from

a single ancestral species, the wolf.

Dog breeders select those pups

that have the characteristics

Nature, of course,

that are best suited

to a particular environment.

But the process is essentially the same.

And in both cases,

it has produced astonishing variety.

In effect,

many of these different breeds

could be considered different species,

because they do not, indeed,

they cannot interbreed.

For purely mechanical reasons,

there's no way in which a Pekingese

can mate with a Great Dane.

Of course, it's true that,

if you used artificial insemination,

almost any of these breeds.

but that's because human beings

have been selecting between dogs

for only a few centuries.

Nature has been selecting

between animals for millions of years,

tens of millions,

even hundreds of millions of years.

So what might have started out

as we would consider to be breeds,

have now become so different

they are species.

Darwin, sitting in Down House,

wrote to pigeon fanciers

and rabbit breeders

asking all kinds of detailed questions

about their methods and results.

He himself, being a country gentleman

and running an estate,

knew about breeding horses

and sheep and cattle.

He also conducted careful experiments

with plants in his greenhouse.

But Darwin knew that the idea

without divine intervention

would appall society in general.

And it was also contrary to the beliefs

of his wife, Emma,

who was a devout Christian.

Perhaps for that reason, he was keen to

keep the focus of his work scientific.

He made a point of not being drawn

in public about his religious beliefs.

But in the latter part of his life

he withdrew from attending church.

On Sundays, he would escort Emma

and the children here

to the parish church in Down,

but while they went into the service,

he remained outside

and went for a walk

in the country lanes.

Perhaps because he feared his theory

would cause outrage in some quarters,

he delayed publishing it

But he wrote a long abstract of it.

And then, on July 5th 1844,

he wrote this letter to his wife.

"My dear Emma, I have just finished

this sketch of my species theory".

Some sketch. It was 240 pages long.

in case of my sudden death,

"that you will devote 400

to its publication".

He then goes on to list

his various naturalist friends,

and check it,

and he ends the letter, charmingly,

"My dear wife,

yours affectionately, C. R. Darwin".

He continued to accumulate evidence

and refine his theory

for the next 14 years.

But then his hand was forced.

In June 1858, 22 years after he got back

from the Galapagos,

here in his study in Down,

he received a package

from a naturalist who was working

in what is now Indonesia.

His name was Alfred Russel Wallace.

He had been corresponding with Darwin

for some years.

But this package was different.

It contained an essay that set out

exactly the same idea as Darwin's...

of evolution by natural selection.

The idea had come to Wallace

as he lay in his hut

semi-delirious in a malarial fever.

But although his idea of natural

selection was the same as Darwin's,

he had not spent 20 years gathering

the mountain of evidence to support it,

as Darwin had done.

But whose idea was it?

In the end, the senior members

of the Linnean Society

decided that the fairest thing

was for a brief outline

of the theory from each of them

to be read out one after the other,

at a meeting of the society here

in Burlington House, in London.

The Linnean, then, as now,

was the place where scientists studying

the natural world held regular meetings

about their observations and thoughts.

The one held on July 1 st 1858

was attended by only about 30 people.

Neither of the authors were present.

Wallace was 10,000 miles away

in the East Indies.

And Darwin was ill and devastated

by the death, a few days earlier,

of his infant son.

So he was still at his home in Kent.

As a consequence, the two papers

had to be read by the secretary.

And as far as we can tell, they made

very little impression on anyone.

Darwin spent the next year

writing out his theory in detail.

Then he sent the manuscript

to his publisher,John Murray,

whose firm, then as now,

had offices in Albermarle Street,

just off Piccadilly, in London.

Murray was the great publisher

of his day,

and dealt with the works of Jane Austen

and Lord Byron

whose first editions

still line these office walls.

Darwin regarded his work

as simply a summary,

but, even so, it's 400 pages.

It was published on November 24th 1859.

This is not a first edition,

more's the pity.

First editions are worth, literally,

hundreds of thousands of pounds.

This is a sixth edition. My copy,

which I bought as a boy,

at 18, I notice, and it cost me

the princely sum of one shilling.

The first edition, of 1,250 copies

sold out immediately.

Translation

Translate and read this script in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this screenplay to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Charles Darwin and the Tree of Life" Scripts.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 25 Feb. 2025. <https://www.scripts.com/script/charles_darwin_and_the_tree_of_life_5315>.

Discuss this script with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In