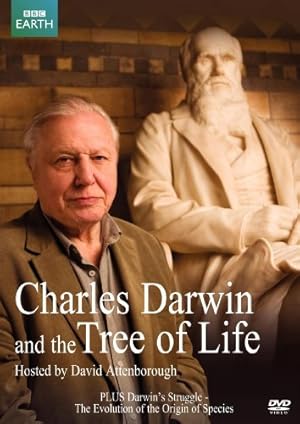

Charles Darwin and the Tree of Life Page #3

- Year:

- 2009

- 59 min

- 8,120 Views

and it went for a reprint, and then

another reprint and another reprint.

It's a book that contains very few

technical terms.

It's easily understood by anybody.

And, predictably, it caused an outrage,

not only throughout this country,

but indeed all the civilised world.

What scandalised people most, it seems,

was the implication that human beings

were not specially created by God

as the book of Genesis stated, but were

descended from ape-like ancestors.

A notion that provided a lot of scope

for cartoonists.

The leaders of the Church,

headed by Samuel Wilberforce,

the Bishop of Oxford, attacked it

on the grounds that it demoted God

and contradicted the story of creation

as told by the Bible.

"That Mr Darwin should have wandered

"from this broad highway

of Nature's works

"into the jungle of fanciful assumption

is no small evil. "

"I have read your book

with more pain than pleasure.

"It is the frenzied inspiration

of the inhaler of mephitic gas. "

"Fails utterly. "

Darwin's theory implied that life

had originated in simple forms

and had then become

more and more complex.

He knew perfectly well

that the whole idea of evolution

raised a lot of questions.

In fact, some of those questions

would not be answered

until comparatively recently.

But in his own time, many distinguished

scientists raised what seemed to be

insuperable difficulties.

was Richard Owen,

the man who, 20 years earlier,

had named the extinct ground sloth

in honour of Darwin.

Over the years, the two men

had developed a deep personal dislike

of one another,

and had quarrelled frequently.

It wasn't that Owen thought

that the story of the Garden of Eden

was literally correct, but nonetheless

he was a deeply religious man.

He had, after all,

ensured that his museum,

which would display

the wonders of creation,

echoed, in its design,

the great Christian cathedrals

of mediaeval Europe.

And Owen knew about

the diversity of life.

Indeed, he had spent

his whole career cataloguing it.

But even so, he refused to believe

that a species could change over time.

He, and other pioneer

Victorian geologists,

as they established

their comparatively new science,

recognised that the outlines

of the history of life

could be deduced by examining

the land around them.

Look at these rocks

in Northern Scotland.

We know from fossils that were

associated with them

that they are very ancient.

And they are sandstones.

Compacted sand that was laid down

at the bottom of the sea

layer upon layer upon layer.

But look how many layers there are.

Clearly, those at the top must have been

laid down after those beneath them.

So, as you descend from layer to layer,

you are, in effect, going back in time.

So a fossil species,

if it comes from a particular layer,

is of a particular age.

And if you can recognise each one,

then you can begin to piece together

the outlines of life's history.

My krafta.

The ability to identify fossils and

place them in their geological time zone

was still an essential skill when

I was at university a century later.

We worked our way through drawers,

like these,

which are full of fossils

of one sort or another.

But none of them had labels.

Only numbers.

So you were expected to be able

to pick up one

and say, "Yes, that's a belemnite".

Actually which belemnite it is,

I can't remember now.

And when you came to

your practical exam,

one of these and say,

"Okay, what's that?"

And you either knew or you didn't.

And the way you knew was because of all

the work you did in drawers like these,

hour after hour.

Owen did not deny the sequence in which

all these different species appeared,

but he believed that each was separate,

each divinely created.

Darwin's theory, however, required

that there should be connections,

not just between similar species,

but between the great animal groups.

If fishes and reptiles

and birds and mammals

had all evolved from one another, then

surely there must be intermediate forms

And they were missing.

And then, just two years after the

publication of The Origin of Species,

Richard Owen himself purchased the most

astonishing fossil for his museum.

It had been found

in this limestone quarry in Bavaria.

The stone here splits into flat,

smooth leaves

that have been used as roofing tiles

since Roman times.

Most are blank, but occasionally,

when you split them apart,

they reveal a shrimp or a fish.

It's almost impossible to resist

the temptation of pulling down

almost every boulder you see

and then opening it like a book.

to look at each unopened page

to see whether, maybe,

it contains yet another fossil.

But this fossil

was something unprecedented.

It is still one of the greatest

of the treasures that are stored

in the Natural History Museum.

And this is it.

It's called Archaeopteryx.

It has unmistakable feathers

on its wings

and down its tail.

So Owen had no hesitation

in calling it a bird.

But it was unlike any other bird

that anyone knew of,

because it had claws

on the front of its wings,

and as was later discovered, it didn't

have a beak but jaws with teeth in it,

and a line of bones

supporting its tail.

So it was part reptile, part bird.

Here was the link between those two

great groups that was no longer missing.

Gosh, you really can see

the filaments there.

Other examples of the same creature

show its feathers even more clearly.

We know from the bones

of the Archaeopteryx

that it was at best a very poor flyer.

So, it's not surprising

that eventually it was superseded

by more modern, more efficient birds.

And that's the fate of these links

between great groups.

Eventually, they become extinct.

And the only way we know they existed

is from their fossilized remains.

Even so, there is a bird alive today

that illustrates the link

between modern birds and reptiles.

The hoatzin nests in the swamps

There are caiman in the water beneath,

ready to snap up any chick

that might fall from its nest.

So, an ability to hold on tight

is very valuable.

And the nestlings have

a very interesting way of doing that.

The young still have claws on the front

of their wings as Archaeopteryx did.

Here is vivid evidence that the wings

of birds are modified forelegs

and once had toes with claws on them.

There's another creature alive today

that represents a link

between the great animal groups.

A descendant of a group of reptiles

that took a different

evolutionary course

and evolved not feathers but fur,

the platypus.

When specimens of this creature

first reached Europe from Australia

at the very end of the 18th century,

people refused to believe their eyes.

They said it was a hoax.

Bits and pieces of different creatures

rather crudely sewn together.

And, yet, in a way,

those early sceptics were right.

Translation

Translate and read this script in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this screenplay to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Charles Darwin and the Tree of Life" Scripts.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 25 Feb. 2025. <https://www.scripts.com/script/charles_darwin_and_the_tree_of_life_5315>.

Discuss this script with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In