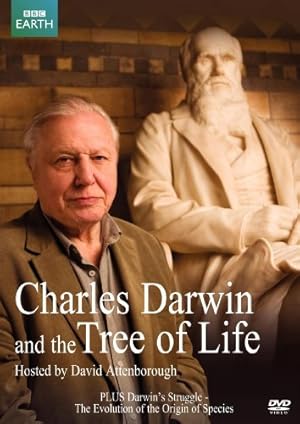

Charles Darwin and the Tree of Life Page #4

- Year:

- 2009

- 59 min

- 8,122 Views

The platypus is the most extraordinary

mixture of different animals.

It's part mammal and part reptile.

And so it can give us some idea of

how the first mammals developed.

When it comes to breed,

it does something that separates it

from all other mammals except one.

In its nest, deep in the burrow,

it lays eggs.

It's this that links the platypus

with the reptiles.

This that entitles it to be regarded

as the most primitive living mammal.

So, the links between

the great animal groups

are not, in fact, missing, but exist

both as fossils and as living animals.

Although the fossil record

provides an answer

to the problem of missing links,

it also posed a major problem.

It started very abruptly.

The earliest known fossils

in Darwin's time

came from a formation

called the Cambrian.

And there were two main kinds.

These, which look like fretsaw blades

and are called graptolite,

and these, like giant wood lice,

which are called trilobites.

Could it really be

that life on Earth started

with creatures as complex as these?

As a boy,

I was a passionate collector of fossils.

I grew up in the city of Leicester,

and I knew that in this area,

not far from the city,

called Charnwood forest,

there were the oldest rocks

in the world.

Older even than the Cambrian.

So, therefore, by definition,

they would be without fossils.

There was no point in me looking

for fossils in these ancient rocks.

There were, it's true,

very rarely, some rather odd shapes

in these rocks, like this one here.

But they were dismissed as being

some kind of mechanical aberration.

I mean, after all,

how could there be anything living

in these extremely ancient rocks?

And then, in 1957,

a schoolboy with rather more patience

and perspicacity than I had

found something really remarkable.

And undeniably

the remains of a living creature.

And here it is in Leicester museum,

where it's been brought

for safe-keeping.

It's called Charnia.

Who could doubt that this

is the impression of a living organism?

It has a central stem,

branches on either side.

In fact, it seems to have been

something like the sea pens

that today grow on coral reefs.

Since its discovery,

a whole range of organisms

have been found in rocks

of this extreme age.

Not only here in the Charnwood forest

but in many other

different parts of the world.

Fossil hunters searching these rocks

in the Ediacara Hills of Australia

had also been discovering

other strange shapes.

At first, many scientists refused

to believe that these faint impressions

were the remains of jellyfish.

But, by now, enough specimens

have been discovered

to make quite sure that,

that indeed is what they are.

So, now we know

that life did not begin suddenly

with those complex animals

of the Cambrian.

It started much, much earlier,

first with simple microscopic forms,

which eventually became bigger, but

which were still so soft and delicate

that they only very rarely

left any mark in the rocks.

The question of the age of the Earth

posed another problem

for Darwin's theory.

In the 17th century, an Irish bishop

had used the genealogies

recorded in the Bible

that lead back to Adam

to work out that the week of Creation

must have taken place

in the year 4004 B.C.

That may seem to us to be

a very naive way of doing things,

but what other method was there anyway?

The Victorian geologists

had already concluded

that the Earth must be

millions of years old.

But how many millions, no one could say.

Then, less than 50 years

after the publication ofThe Origin,

a discovery was made in what seemed

a totally disconnected branch of science

that would ultimately

provide the answer.

A Polish woman working in Paris,

Marie Curie,

discovered that some rocks

contained an element called uranium

that decays over time at a steady rate

through a process called radiation.

Today, a century after she made

her extraordinary discovery,

the method of dating

by measuring changes in radioactivity

has become greatly refined.

This is a sample taken from those

very ancient rocks in Charnwood forest.

And these tiny crystals

are revealed to be

562 million years old.

That provides more than enough time

for natural selection

to produce the procession of fossils

that eventually leads to the

living animals and plants we know today.

But there was another objection.

If all animals within a group

have a common origin,

how is it that some kinds of animals

are distributed

throughout the continents of the world

except for Antarctica?

How is it that, for example,

frogs in Europe and Africa

are also found here in South America

on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean?

Bearing in mind

that frogs have permeable skins

and can't survive in sea water.

Darwin himself had

a couple of suggestions.

One was that they might

have floated across accidentally

on rafts of vegetation.

And the other is that maybe there were

land bridges between the continents.

But even he was not convinced

by either explanation.

Even as late as 1947,

when I was a geology student

here at Cambridge,

there was no convincing explanation.

It's true that back in 1912,

a German geologist had suggested

that at one time

in the very remote distant past,

all the continents of the Earth

that we know today

were grouped together

to form one huge supercontinent.

And that over time this broke up

and the pieces drifted apart.

That would have provided an answer.

But when I asked the professor of

geology here, who was lecturing to us,

why he didn't tell us about that

in his lectures,

he replied rather loftily, I must say,

"When you can demonstrate to me

that there is a force on Earth

"that can move the continents

by a millimetre, I will consider it.

"But until then, the idea

is sheer moonshine, dear boy".

But then in the 1960s, it became

possible to map the seafloor in detail

and it was discovered not only

that the continents have shifted

in just the way that

the German geologist had suggested

but that they were still moving.

New rock wells up from

deep below the Earth's crust

and flows away on either side

of the mid-ocean ridges,

carrying the continents with it.

Amphibians had originally evolved

on this supercontinent

and had then travelled on each

of its various fragments

as they drifted apart. Problem solved.

Perhaps, the biggest problem of all

for most people

was the argument put forward

for the existence of God

at the beginning of the 19th century

by an Anglican clergyman

called William Paley.

He said, supposing you were walking

in the countryside

and you picked up something like this.

You would know from looking at it that

it had been designed to tell the time.

There must, therefore, be a designer.

And the same argument

would apply if you looked

at one of the intricate structures

found in nature, such as the human eye.

And the only designer of the human eye

could be God.

Translation

Translate and read this script in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this screenplay to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Charles Darwin and the Tree of Life" Scripts.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 25 Feb. 2025. <https://www.scripts.com/script/charles_darwin_and_the_tree_of_life_5315>.

Discuss this script with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In