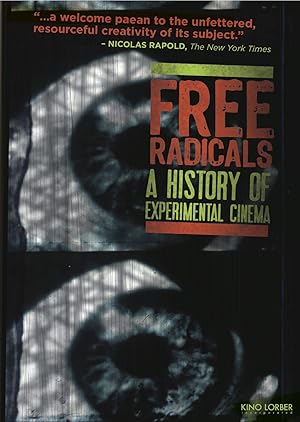

Free Radicals: A History of Experimental Film Page #4

Later I did another

documentary with Stan.

And he invited us up to MI to film him in a space that he

called the Architecture Room.

It was the size of

a big living room,

floor to ceiling, all four walls,

banks of electric equipment,

all in service to a little

monitor on a table with a keyboard.

Suppose we consider the computer

a tool, very much like the hammer,

although we don't know what to

make with it or what to do with it.

So for the last two years

I've been here at MI as an artist fellow at the Center

for Advanced Visual Studies,

and the attitude I've had is to explore

what these new technologies mean to us.

I believe that there's an

enormously important future

in the development of new

communications systems that artists,

literally all around the

world will try to deal with.

You could draw a

picture of a house,

the way a child would

draw a picture of a house,

and then you could enter a command

which would rotate that 360 degrees.

Jesus was Stan excited!

This was a big deal in those days.

I remember at one point

in the filming a dog

walked through the architecture room.

Nobody paid the slightest attention.

Everyone was glued to that monitor.

I'd like to show

you now a small film

that I actually jokingly

call computer fingerpainting,

which uses a system

very similar to this one

that we just are working with now.

It's called Symmetricks.

Your children, 14-15 years old

will be able to work with

this in probably 3-4 years.

Art schools of the future

will teach programming

as much as they teach life drawing.

There's a whole new

definition of communications

which are now in our hands potentially,

if we can get our hands on them.

I wonder what Vanderbeek

would think now,

where the average iPhone has

more computing power in it

than a million

architecture rooms at MIT.

It was Vanderbeek who coined the

term 'underground cinema' in 1963.

He was a founding member of the filmmaker's

cooperative and even drew the logo.

And like the other

filmmakers, he seeked out ways

to finance his prolific

filmmaking hobby.

I wondered about this

and I asked Jonas Mekas.

I asked him, how a poor

immigrant, working in factories,

could afford to shoot so much film?

During that period I made

Lost Lost Lost and Walden.

I always managed to

buy a roll of film.

I mean, you do all kinds of jobs,

factories, all kinds of places...

You can always afford one roll

of film per month or per week.

On 8th avenue and 50th

street there was a place

that was selling black and

white film for like one dollar.

Everybody said, ah look at the

quality, this black and white,

like washed out, that

interesting quality-

no that's because

the film was outdated!

And you could buy it cheap.

So it was not... it was

cheaper than video today.

Because okay, you do video,

but then you have to edit it,

you need other technologies,

and it's becoming more

expensive than film.

Film was cheap.

Hunger, you know.

Just hunger, man.

Walking one night, walking

home through Chinatown,

man there was a bag of garbage food

in front of one of the restaurants

and spilling out

of it were greasy -

this is going to

disgust you, folks!

greasy spare ribs, cold greasy

spare ribs thrown out in the garbage.

I looked at it, picked up a

couple and began to eat them.

Yeah. That was the worst.

Even though filmmaking

was exciting,

especially so-called experimental

filmmaking was an exciting way to go,

but I could never sell them

to large numbers of people,

and that came as a shock

and a disappointment to me,

I didn't know what the hell to do.

Didn't Len Lye go on

strike as a filmmaker?

Oh he quit making films

and he was very disappointed

because he was given a Brussels

or some prestigious award

which had a little

bit of money with it,

as the most, the best,

avant-garde filmmaker,

but because there was no follow-up

and no real money from that,

he was disgusted that he

got that much attention.

Before his strike, Len Lye had been

working as a filmmaker for hire,

for the British post office.

This was one way experimental

filmmakers could make a living.

He was allowed to experiment

at the post office,

where he pioneered and innovated

in almost every film technique.

This film, Rainbow Dance, using

one of the first color processes,

involved very complex

printing tricks.

This was 1935. While most

films were in black and white,

Lye's film stood out like fireworks

from the features it often preceded.

Audiences loved it.

The Post Office Savings

Bank puts a pot of gold

at the end of the rainbow for you.

No deposit too small, the

Post Office Savings Bank.

OK, well we'll loosen it

all and get in what we can.

Lye segued into the art

world through his sculptures,

but his films were never

part of the art world.

Galleries couldn't sell films.

The filmmakers found

themselves in a no-mans-land,

between the commercial film

industry and the art world.

The galleries are hostile.

Its place is artificial.

I mean, people doing this thing like

making limited numbers of prints.

For what reason? Only to make

something artificially rare.

It's horrible. It's a lie.

The modern art museums always had

the filmmaker part of the museum -

it's probably still true

- are the poorest part of the museum.

I don't know how long that will

last but I'm sure it's still true.

They don't, they aren't

given nearly as much money

as the main part of the art museum,

because the art museum can still

sell these unique pieces to people

because art collecting

is anal, you know?

I thought these

films were great art.

I wanted galleries and

museums to recognize that.

So in 2005 I started a gallery

to try and show experimental

films in the art world.

Here is the FIAC art fair in Paris,

in which I invited Jonas, Peter

and others to show their work.

Peter Kubelka started making

films in Vienna in the 50s.

He invented a new approach to

filmmaking called metric montage,

based not on the content of

the shots but on their length.

He made ADEBAR in 1957,

showing it both as a

film and as a sculpture.

The work was 50 years old when

I suggested we try selling it.

In fact, when I showed the film

in Alpbach, the print broke.

And this film cannot miss a frame.

If you miss a frame or two,

the rhythm will be gone.

So I said, no more and the print

will only live further like this.

Then I put it on

these wooden things,

and it would move in the wind,

and then during the night it got wet

and then the wind would tear it apart,

then the people came and

started to snip off pieces...

This is for example, this

is the most sentimental shot.

It starts as the movement.

It starts with a man and a woman

and then the woman dances

out and the man remains alone.

See, this is the Hollywood departure,

but Hollywood takes 90 minutes for that

and I take exactly 52 frames.

A little more than two seconds.

-Yeah, a little more than two seconds.

Translation

Translate and read this script in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this screenplay to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Free Radicals: A History of Experimental Film" Scripts.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 30 Jan. 2025. <https://www.scripts.com/script/free_radicals:_a_history_of_experimental_film_8556>.

Discuss this script with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In