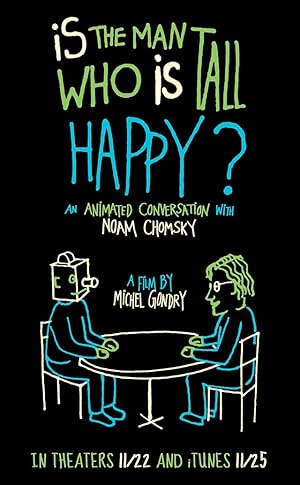

Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy? Page #2

working with others.

There was no grading, you know,

but you were encouraged

to pursue your own interests

and... within a structure

that was established,

so you did, you know, learn

the things you had to learn.

But, I mean, you were all

pursuing your own interests

and often working with others.

In fact, I didn't...

I wasn't even aware

that I was a good student

until I went to high school.

I went from this relatively

free, creative,

exciting environment

to a pretty regimented

and academic high school

where everyone was ranked

and you'd do exactly

what you were supposed to do

and everyone's trying

to get into college and so on.

And then I discovered

I was a good student.

I mean, I knew

I had skipped a grade,

and everyone else knew

I'd skipped a grade,

but nobody else...

The only thing anyone noticed was,

I was the smallest kid

in the class,

but it didn't mean anything

aside from that.

And I can remember

I barely remember high school.

It's kind of like a black hole.

And do you think competition

is counterstimulating?

It shouldn't be.

What's the point of being

better than someone else?

And where was this school?

Right outside the city limits

of Philadelphia.

It was in a... kind of

an open countryside.

So, you know, by the time

I was old enough to,

my best friend and I

would spend Saturday

riding our bikes

all over the countryside.

Did you kept friend from this age

all during your life?

We sort of separated

by high school, you know,

went our separate ways.

Well, you spent a lot of time

on your own.

With my father by the time

I was 10 or 11 or so,

every Friday night, for example,

we would read Hebrew classics,

you know,

19th-century literature, essays.

It was just part of the routine.

And incorporating the emerging,

reviving Hebrew culture,

that was all of their lives.

I mean, that's what they were

devoted to:

the revival of the language,

the culture,

the Palestinian community,

this Hebraic revival that...

Did you say Palestinian community?

Well, you know, it was pre-Israel,

so it's a Jewish community

in Palestine.

Okay, okay.

I suppose by now, my father

would be called an anti-Zionist.

He was then

but for him, it was

a cultural revival, basically,

not particularly interested

in a Jewish state.

Mm-hmm.

Do you remember

if you had an ambition

for your future as a child?

A lot of crazy ambitions.

I remember once telling my mother

that I had decided

that when I grew up,

I wanted to be a taxidermist.

Don't ask me why.

So since I'm ignorant, I got

the luck to discover Descartes.

I mean, I knew who Descartes was,

but I read him after I read you,

and I noticed he give you the tools

to doubt what he's saying.

It's like the opposite

of dogmatism.

I mean, that, you know, ought to be

Whether it's children

or graduate students,

they should be taught

to challenge and to question.

Images that come from

the enlightenment about this

say that teaching should not be

like pouring water into a vessel.

It should be

like laying out a string

along which the student travels

in his or her own way

and maybe even questioning

whether the strings

in the right place.

And, you know, after all,

that's how modern science started.

For thousands of years,

it was accepted by scientists

that objects move

to their natural place.

So a ball goes to the ground,

and steam goes to the sky.

These things are kind of

like common sense,

and they were taken for granted

for literally thousands

of years, from Aristotle.

And it wasn't until Galileo

and the modern

scientific revolution

that scientists decided to be

puzzled by these obvious things.

And as soon as you start

to question things,

you see nothing like that

makes any sense.

or, you know,

even just learning,

serious learning,

comes from asking,

"Why do things work like that?

Why not some other way?"

All right, you find that the world

is a very puzzling place,

and if you're willing

to be puzzled,

you can learn.

If you're not willing to be puzzled

and just copy down what you're told

or behave the way you're taught,

you just become a replica

of someone else's mind.

Some of the technical work

I'm doing now

is initiated

by my suddenly realizing

that assumptions

that have been standard

throughout modern history

of generative grammar

but, in fact, throughout the

traditional study of language

just have no basis.

And when we ask, "Okay,

then why do we assume them?"

you have to look for a basis,

and lots of avenues open up,

and that happens constantly.

And do you remember

when you start to build

your own voice or your own

philosophy, in a way?

And could you describe

how this process happened?

It's a constant process,

and it probably starts

with my not wanting

to eat my oatmeal, you know.

Why, you know?

Uh-huh.

And in any kind

of scientific inquiry,

any kind of rational inquiry

that's striking in science,

you have a conception

If you look at the empirical data,

they're usually at least

partially recalcitrant.

Things don't fall into place.

So you typically are working

with a conflict

between a conception

of the way things ought to work

in terms of elegance,

simplicity, naturalness

and a look at the messy way

in which things do seem to work.

The Galilean revolution,

which was a real revolution

in the way of looking at the world,

for one thing because of

the willingness to be puzzled

about what seemed to be

simple things,

it's a hard move to make.

In the case I mentioned,

it was 2,000 years.

You know, smart people.

They said that nature is simple

and it's the task of the scientist

to show that it's simple.

And if we've not been able

to do that,

we've failed as scientists.

So if you find

irreducible complexity,

you just haven't understood.

Well, that's a pretty good

guideline.

And it does turn out to be

a very effective driving element

in inquiry,

because there's good reasons

why things ought to turn out

to be simple, you know.

I mean, for Galileo

great scientists...

you know, Huygens, others,

Bernoulli, up through Newton...

you know, this kind of

classic period

of modern science...

there was a very clear

concept of intelligibility.

The goal of science was to show

that the world is intelligible.

And intelligible meant something.

It meant something

that an artisan could create,

like gears and levers,

and something like...

A model was these,

let's say, medieval clocks,

you know,

which did all sorts

of amazing things.

Now, that goes

right through Newton.

It's called

the mechanical philosophy.

"Philosophy" just meant "science,"

so it's mechanical science.

And that's the goal.

Translation

Translate and read this script in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this screenplay to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?" Scripts.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 22 Feb. 2025. <https://www.scripts.com/script/is_the_man_who_is_tall_happy_10984>.

Discuss this script with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In