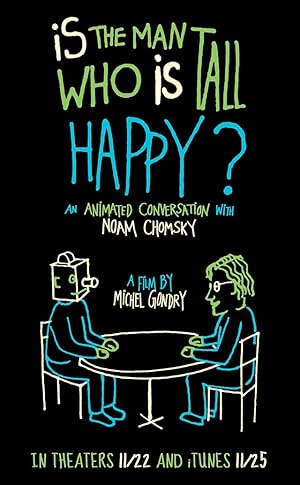

Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy? Page #3

I mean, Galileo,

at the end of his life,

was kind of distraught

because he was not able

to construct mechanical models

of the tides

and the motion of the planets

and so on,

so he felt his life...

scientific life had failed.

But then it went on.

Finally get to Newton,

and Newton demonstrated,

to his dismay,

that the world doesn't work

like a machine,

that there are

what his scientific colleagues

called occult forces,

namely attraction and repulsion,

which don't operate by contact.

So you can attract things

at a distance,

which was just unintelligible.

Newton himself thought

that this was what he called

an "absurdity"

which no person with any scientific

understanding could ever believe.

There were just inherent mysteries

which were beyond

our cognitive capacities.

Well, that was correct, and that

was a real shocking discovery.

It has now been absorbed.

So to talk about

the current stage is misleading

if you're thinking

about emerging fields

like cognitive science,

'cause we're not in that stage.

We haven't got

to the Galilean stage yet.

Me, I work like a machine.

I know this sequence

is quite a struggle.

And, believe me, it's taking me

forever to animate it.

So I'll take a break.

Noam kept coming back

to Galileo, Newton,

the enlightenment,

and I tried very hard

to keep it short,

but it seems endless.

However, this is

a very important part, in fact,

and I must get through it.

I think that Noam is

telling me what it takes

to do true science...

something to do with ideas,

creativity and rigorous

observation of nature,

and the willingness

to be proven wrong

and start the experiment again

all over at any time.

Richard Feynman,

the great physicist,

often talked

about science integrity

and said you should always publish

the result of your experiment,

especially when

they prove you wrong.

He also had a funny story

about a good scientist

that was ignored.

In 1937, Young, he was called,

was trying to teach a rat

to count three doors

to get some food.

So he would place the food

each time in a maze

three doors away from the rat

to get it to count three doors.

He would place the rat

in a different place each time,

with the cheese three doors away.

But the rat never counted

the doors.

He always went right to the door

where the food was placed

the time before.

No matter where Young placed

the rat and the food,

the result was the same.

He thought the rat must

recognize a detail on the door,

so he repainted them all

identically.

Still the same result.

He then thought the rat

could still smell the food

from where it was the previous

time, so he put some chemical

to wipe any possible

remaining smell.

Still the rat went

to the exact same door.

Maybe the rat could notice

some light from the lab

and use them as a guide,

so he covered the maze.

Still the same result.

He eventually found out

that the rat could tell

by the way the floor sounded

when he was running

down the corridor.

So he put the whole maze on sand.

The rat couldn't tell anymore

and had to learn

to count the doors.

Feynman called this experiment

an A class experiment,

because Young had to go through

all the possible steps

before he could affirm

it was conclusive,

a rigor that he felt

was unfortunately uncommon

in the science the way it was

conducted at his time.

Now I am just adding stuff

that is not even from Noam.

But I've put a loop under it

so it is not so much work.

The truth is that I am

frantically going through

this animation,

and it has been two years

since I started,

so Noam is now 84.

I neglect my appearance,

and I should be focusing

on the film I am preparing,

L'cume des jours,

but I won't stop.

I must finish the film

and show it to Noam before...

well, before he's dead.

My room is a pile

of animation paper,

my mother is at the hospital,

but I only care

about Noam's health,

only to show him the finished film.

This is childish

and unscientific but true.

A few session we did before,

we talked about evolution,

and you were very skeptical,

and I thought...

I'm not skeptical about evolution.

There's a common confusion

outside of serious biology.

I mean, natural selection

is a factor in evolution.

No serious biologist doubts that.

But it's one of many factors.

For example, mutation is a factor.

I mean, there are

many other factors.

For example, if you just take a look at

our... you know, our own genetic endowment,

a lot of it comes

from transposition.

When you talk

about the endowment...

the endowment?

I'm sorry. How do

you say endowment?

When you're born with what...

Well, like a...

- Innate?

- Yeah.

But do you use the

word "endowment"?

How do you spell it?

Write it on the blackboard.

Endowment.

- Endowment.

- Oh, endowment.

Sorry.

So you think that we have a way

to comprehend the world

within ourself

and we can only comprehend

the world up to this limit...

That's just Hume.

That's Newton and Hume.

So you try to discover,

what is this cognitive endowment

that we have?

That it is

a fixed cognitive endowment

is not really arguable

unless you think we're angels.

But if we're part

of the organic world,

we have fixed capacities,

just like I can't fly, you know.

These capacities have

a certain scope,

and they have certain limits.

That's the nature

of organic capacities.

Then comes the question,

"Okay, what are they?"

In fact, one of the striking things

is what I just mentioned.

We... our cognitive endowment

sort of compels us

to regard the world

in mechanical terms.

We know that's wrong,

but we can't help

seeing the world like that.

If you look at the moon

rising in the early evening,

at the horizon, it's big,

and then it gets smaller

and smaller.

It's called the moon illusion.

We know it's not true,

but you can't help seeing it.

Well, I thought of it a lot,

and I know it's one of the paradox,

but I think our brain zoom...

It's like if you see the world

through a window

which is at a far distance

and you will see a bridge

in the distance

and the window delimits

your attention,

then you would feel the bridge

is much bigger than what it is.

But now you're trying

to give an explanation,

and there's been a lot of work

on what the explanation is.

But whatever...

and it's not so trivial,

but whatever the explanation is,

we can't help seeing it, okay?

We just see it,

just like we can't help thinking

that the world works by

physical interaction, contact.

Some other part of our brain

tells us it's not true

because of theories

that have been developed

that say it can't work like that.

But that can't change our

perception and interpretation,

'cause that's just fixed.

Okay, I'm trying to visualize...

or I guess it's not visualizable...

but this endowment.

So we see a tree,

and we understand it's a tree.

Does it mean that our brain

is equipped

with a fixed capacity

Translation

Translate and read this script in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this screenplay to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?" Scripts.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 22 Feb. 2025. <https://www.scripts.com/script/is_the_man_who_is_tall_happy_10984>.

Discuss this script with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In