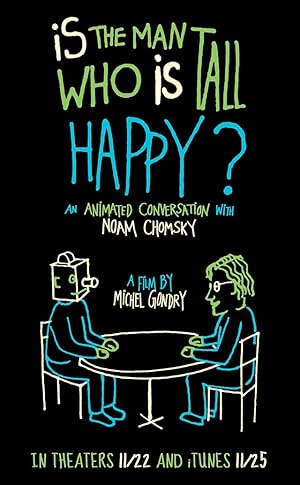

Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy? Page #4

that tells us,

"This is a tree"?

Here's another question

where it's good to be puzzled.

How do we identify

something as a tree?

It's not so simple.

So, for example,

if you plant a tree...

say, a willow tree,

which is a good example...

it grows.

And at some point,

you cut a branch off it,

and you put that branch

in the ground.

Suppose it grows

to the original tree.

is cut down.

Is that new one

the same willow tree?

Why not?

It's genetically identical,

it has all the same properties,

but we know it's not the same tree.

Why not?

I mean, and if you go further,

it turns out

our concept of a tree or a rock

or a person or anything

is extremely intricate.

And furthermore...

See, here's what I think.

It's just a classic error

that runs right through

philosophy and psychology

and linguistics

right up to the moment.

That's the idea that words...

say, meaning-bearing elements,

like, say, "tree" or "person"

or, you know, "John Smith"

or anything...

pick out something

in the extramental world,

something that a physicist

could identify

so that if I have a word...

say, "cow"...

it refers to something,

and a, you know, scientist

knowing nothing about my brain

could figure out

what counts as a cow.

That's just not true.

That's why you have classic books

with names like Words and Object...

Word and Object,

Quine's major book,

or Words and Things,

Roger Brown's major book.

That referentialist assumption

I mean, it's true of animals.

Like, as far as we know

of animal communication,

yeah, that's actually true.

But for humans, it's simply untrue,

and, furthermore,

And that poses

a huge evolutionary problem.

Where did that come from?

It imposes an acquisition problem,

a descriptive problem,

an evolutionary problem.

because everyone assumes,

"Well, there's just

a relationship."

That's like assuming things move

We're never going to have a real

understanding of semantics

unless those illusions

are thrown out.

Well, something that always

struck me since I was young

is, like, you get

the representation

of the world by symbols first.

Like, logically,

you would see a dog,

and then you would see

a drawing of a dog

and make the connection.

But in your life, you get exposed

to the representation of a dog

in a very, actually,

simplified way,

and then you go to...

or let's say you go outside

and you see a real dog.

That's not the way it works.

Yeah, that's very

commonsensical, just false.

No, I'm not... I'm saying

it's how it's exposed, like...

It makes sense,

and every work on philosophy

or linguistics

says exactly that.

It just happens to be false.

And, furthermore,

every infant knows it.

Now, fairy stories are based

on the fact that it's false.

Like, take a fairy story

that any child understands.

No, I'm not saying the child

believes it's a real dog.

What I'm saying...

That's not the point.

We do not identify dogs

in terms of

their physical characteristics.

As you can see,

I felt a bit stupid here.

Let me explain.

I think I couldn't get

Misuse of words

I mean aggravated my attempt.

I was simply expressing

that in life,

we first encounter image

of certain things,

such as animals,

the real thing.

For instance, I saw

many picture of a tiger

before I saw a real one in a zoo.

There is nothing to argue

about that,

but Noam kept saying it was false

because of my use

of the word "representation."

I'm pretty sure

that he understood it

as mental representation,

as I was just talking

of an image in a book.

Nevertheless, it gave him

the opportunity

to deepen his argument,

which is hard to understand,

so I kept the whole thing,

even though I look stupid.

Meanwhile, I decided to recycle

some of my drawings,

since he was making

the same point again.

We do not identify dogs

in terms of

their physical characteristics.

We identify dogs, for example,

in terms of a property

of psychic continuity.

Like, if a witch turns a dog

into a camel

and then some fairy princess

kisses the camel

and it turns back to a dog,

it's been a dog all along,

even when it looked like a camel.

I mean, that's the basis

of fairy tales.

I was not saying that it's...

But psychic continuity

is not a physical property.

It's a property

that we impose on things.

So, therefore, there is no hope

for finding away

of identifying the things

that are related to symbols

by looking

at their physical properties.

They're individuated,

they're identified

in terms

of our mental constructions,

so they're basically

mental objects.

Mm-hmm.

And that means

the whole referentialist concept

has to be thrown out.

Now you have to look

at the relation of language

to the world

in some different fashion.

And so... and do you think

we constructed the world

in mirroring this image

we had in our mind?

We do it, but we don't do it

the way philosophers

We certainly do it.

So, for example, sure,

we see the world

and rivers and so on,

but then the question is,

"Well, what are those concepts?"

Now, the standard assumption is,

those concepts are linked

to physical, identifiable

physical things

in the extramental world,

and that assumption is just false.

And unless we rid ourselves

of that assumption,

we won't be able to understand

the way thought and language

relates to the world.

But that's a topic

that's just taboo

in philosophy and psychology.

So they're stuck.

They're like mechanics pre-Galileo,

where everything went

to its natural place.

Well, as long as you keep

to that for thousands of years,

you're never going to understand

the mechanics of the world.

That's why I think

these are the kinds of reasons

why it makes very good sense

to think back

to the earliest stages

of the scientific revolution.

Not Einstein;

that's too sophisticated.

Let's go to the earliest stages,

where people had that incredible

intellectual breakthrough

and they said, "Let's be puzzled

about what seems obvious."

So why should we take it

to be obvious

that if I let go of a ball,

it goes down and not up?

I mean, it's sort of obvious,

but why?

Well, as soon as you're willing

to ask that question,

you get the beginnings

of modern science.

If you're not willing

to ask that question,

you say, "Well, it goes down;

it belongs on the ground,"

no science develops.

Once again, I had posed

I was trying to ask

if the way humans built things

such as cities, art, cars,

and so on

was reflective

of a sort of blueprint

we would carry

within our endowment...

like bees constructing

their hives, for instance.

So next time I met Noam,

Translation

Translate and read this script in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this screenplay to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?" Scripts.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 23 Feb. 2025. <https://www.scripts.com/script/is_the_man_who_is_tall_happy_10984>.

Discuss this script with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In