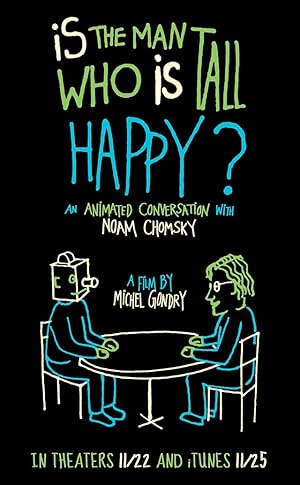

Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy? Page #5

I showed him this animation,

hoping it would help to make sense.

And it did make sense.

At the beginning

of the second interview,

I showed the work

in progress to Noam,

who was quite pleased, it seems.

And I noticed

in the second interview

that he was more receptive

to my ideas.

So I asked my question again,

but using bees and hives

as an example

made it more confusing.

Well, I suppose there is

an interaction.

So if you watch children building,

trying to build a

house with cards...

you know, you stack them up

and you put something on top...

they must have some

initial conception in mind

of what they're planning to do,

but it's certainly altered

by the process.

You see, "Well,

this is not going to stand,

"so I have to rearrange it

and do something

in a different way."

I mean, take the building we're in.

One of its striking characteristics

when you're sitting in my office

is that there aren't

any right angles

in many of the buildings,

so everything's a little skewed.

The... I don't know what was

in Frank Gehry's mind,

but one architect who came through,

working on the... looking at

the structure of the building

suggested to me that it has,

in some respects,

the character

of a three-dimensional version

of a Mondrian painting.

Yes, so I wanted to know

if you have any thinking of

the mechanism of inspiration.

It's a mystery.

It's something common to humans.

You see it in young children.

You see it in scientists.

You see it in carpenters

trying to solve

a complex problem

of how to build a house.

But it's just something

that happens

in all kinds of conditions,

strange conditions.

So, for example, I was watching

a couple of carpenters

working on a summer cottage.

They had kind of an idea in mind

but were kind of going along

to see how it would work.

looked insoluble, you know,

and they sort of took off

for a while,

and then they came back,

and they immediately did it.

And I asked, "How did you do that?"

And they said, "Well,

we went out and smoked some pot,

and it just kind of came to us."

Who knows? That's inspiration.

I wanted to cut out this sequence.

For a short time period,

I had an episode myself

where I indulged into this habit...

very shortly, in fact.

And looking back, it didn't

do me very good at all.

Now that I've said it,

I can keep this sequence.

That's interesting.

For instance, in my case,

I use a lot of my misunderstanding

as a source of inspiration,

and I realize that lately,

like, because my English

is not good,

many times when people talk to me,

I understand something different.

I remember I was talking

to my friend,

and she told me she had made

a model of a boat in a forest,

and I understood

the forest was in the boat,

so I imagined a sort of

vegetable ark of Noah,

Noah's ark.

I think something jarring

takes place,

and that can happen in a class,

for example.

You're lecturing.

A student raises a question,

and suddenly you recognize

that something you thought

was obviously true

has a problem with it.

And for a while,

it may seem insoluble,

but you may take a walk,

or maybe overnight

there's something...

you're sleeping and something comes to you,

and all of a sudden, you just see ways

of looking at the issue

and the world

a little bit differently.

I think that's how,

from childhood on to...

people do creative work.

That's somehow the way it happens.

Actually what's going on,

nobody understands.

In a little clip I'll show you,

you talk in length about how

we try to interpret the world

and how we ought to throw away

what's believed

in linguistics or philosophy.

You say, "Why do we recognize

that this is a different tree

when it's been cut and it grows

and it's identical?"

And since then,

I read about genetics,

and that's a clone, basically.

When you reproduce

as asexual reproduction,

it's a clone.

So it's potentially identical.

But my only... the only answer

I could give

was that I know

it's a different tree

because I saw somebody come and

cut it and then grow again.

So I was thinking, it's probably

less trivial than that.

Well, actually, I think

there's a real point there.

Part of our concept of a tree

has to do

with a certain pretty abstract

notion of continuity.

So the original tree

has a continuous existence

which we impose on it,

because, genetically speaking,

the branch that was cut off

is the same object.

But when it becomes a tree,

it doesn't have

the kind of continuity

that we interpret as continuity.

And a different intelligence

could interpret continuity

quite differently

and say that the new one

is the real tree.

That's our conception

of continuity,

and it's a very complex one.

So, for example,

there's a children's story

which my grandchildren like...

liked when they were little.

It's a story about a donkey

named Sylvester,

and something happens,

and it turns Sylvester into a rock,

and the rest of the story

is the rock Sylvester

trying to explain

to his parents, parent donkeys,

that it's really

their baby Sylvester.

And since children's stories

have happy endings,

something else happens,

and it turns him back to Sylvester,

and everybody's happy.

Well, the children understand

that the rock,

though it has none of

the properties of the donkey,

physical properties,

and has all the properties

of a rock,

is really Sylvester.

And, for example,

if he was turned into a camel later

or suddenly would be a jar,

he's got to come back

and be what he is, Sylvester.

All right, what that tells you

is that without

any instruction, of course,

an infant understands

a certain special kind

of continuity.

It's a very specific kind,

even much more abstract, even,

than in the case of the tree.

But there's a kind of psychic

continuity that we impose on...

It's a part of the interpretation

we impose on the world...

that identifies the objects

that are around us,

whether it's persons or rivers

or rocks or trees

or anything else.

I think I have an example

that maybe make me understand

the concept.

When I meet a friend that

I didn't see for 20 years

and his appearance

is completely different,

first I feel I'm meeting

a different person.

And then, in the course

of the conversation...

it's generally 20 minutes,

30 minutes...

this person become my friend.

And the old image of my friend,

like his picture,

become younger than he is,

so I readjust.

And I was wondering

if this is a phenomenon

that everybody perceive...

All the time. I mean, we...

But is this the same phenomenon

that we apply to objects?

Yeah, the same as with objects,

like the tree or a river.

Or, let's say,

take the Charles River,

the river going past the building.

What makes it the Charles River?

You can have

substantial physical changes,

and it would still be

the Charles River.

So, for example,

you can reverse the direction;

Translation

Translate and read this script in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this screenplay to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Is the Man Who Is Tall Happy?" Scripts.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 23 Feb. 2025. <https://www.scripts.com/script/is_the_man_who_is_tall_happy_10984>.

Discuss this script with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In