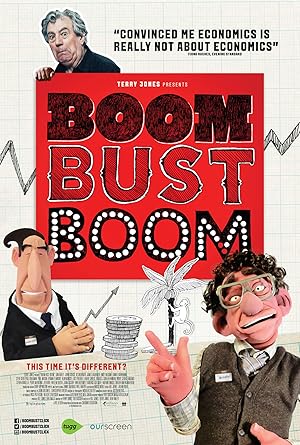

Boom Bust Boom Page #7

our collective rationality. It can be, but it can also be

our collective irrationality, and what was wrong

with economics is that it ruled out

the possibility of irrational outcomes. That's the thing about

free market economics. It is a sort of ideology, and once you

start believing in it, um, it does sort of provide

a sort of framework to explain the world. And they were sort of

trapped inside their

own ideologies, really. JONES: I guess it's about time to factor human nature

into economics. We've come to Puerto Rico to go to that island,

over there, Monkey Island. Monkey Island is a very funny

place in Puerto Rico. It's an island just off

the southeast coast that's home to about

a thousand free-ranging

rhesus monkeys. It's a wonderful place to really observe

monkey behavior in the wild and set up studies to study how irrational

they are sometimes. I think,

'cause I study monkeys, people think

I'm interested in monkeys. But really,

I'm interested in people, and I find that monkeys are

this fascinating window into what people are like. You're down here,

you're watching them, like, hang out with their friends,

and groom, and strive for power,

and getting resources,

and, like, it's just this little

evolutionary microcosm of what we're like without

language and cellphones and all this stuff

of the 21st century. One of the things

we really wanted to do to understand human choice is to see if monkeys would make some of the same smart decisions

and bad decisions. It tells something about

where we came from

evolutionarily and how we're designed

to make decisions. So we introduced the monkeys to their

own new monkey currency. I've one here.

It's a monkey-- It's got little

bite-marks on it. Um, but this is

the monkey currency. We gave it to them

and taught them they could trade these

with humans for food. I believe it's the

only non-human currency

in the world. It is, in fact.

It's probably very--

It's worth a lot, so I'm gonna

keep it in my pocket. SANTOS: First they just traded

with one person. They got good at that.

And now, they get actually,

a choice of people, and they get to pick

who they want to trade from. And each person in the market,

sort of, shows the monkey,

in a little dish, you know, "Here's

what you can buy." And then, uh, the monkey

just gets to choose. And they have

a little wallet of tokens that they can, kind of,

spend between the experimenters. The monkeys meet experimenters who don't always give the same amount of food

that they show. So, they have one amount

of food in their dish, but then, they can, kind of,

vary over time. Um, so, the monkeys can,

uh, say, meet an experimenter who looks like

he's selling one grape, which seems like

a pretty good deal, but every time

the monkey pays him, the monkey actually gets two. So, the monkey's like,

"Wow, this is great ...," right? The monkeys also meet

this other guy and they realize this guy starts

with three grapes. He looks like

he's a really good deal. But every time

the monkey pays him, he takes one away

to give the monkeys just two. Now, both of these guys,

the guy that, you know, looks like he's giving one

but he gives two, versus the guy that looks like

he's giving three but gives two, they ultimately

give the monkey two, right? If the monkey

was being rational, he would just shop randomly

between the two. But what we find

is that the monkeys overwhelmingly shop

at the guy who starts with one

and gives them two-- the guy who looks like

he's giving a bonus-- even though, in fact, the monkeys are getting

the same amount of food. JONES: I'm going back

to the 2008 crash. What-- what effect did

that have on your research? Oftentimes when you

study monkeys, you're studying, uh,

whether the monkeys can do all the smart things

that humans do like tool use and language and all these

incredibly smart things

that people do. And often, the monkeys

come up a bit short. And, so, it was really

a game-changer for the research because we could

now ask the question, not "Are monkeys similar

to humans because monkeys

are so smart?" We could ask,

"Are monkeys similar to humans because in some ways

they're so dumb?" Uh, my colleague, Keith Chen,

is fond of saying, you know, if you plotted

the monkey's data and you didn't know the data

were from a monkey, you would just expect

that they were from

a real human market. The human strategies

we're seeing in real markets are just

evolutionarily really old. They're kind of

leftover strategies

from 35 million years ago. KAHNEMAN: Not only do people value outcomes

as gains and losses, they value losses

a lot more than gains. But it leads to

this bias where losses, these changes that go

in the negative direction, we go in the red, they just feel

emotionally more powerful than these changes

in a positive direction, and that can lead us to do

all kinds of crazy things. We're so trying to avoid these small relative changes

in the red that we do things

like take on more risk. JONES: What can we

do about that? SANTOS: The idea is that

we just have to admit

that we have these biases, that they're old

and hard to get rid of, and then we kind of

have to design policies and markets and systems

around them. I'm quite skeptical about the idea that individuals can

make themselves smarter or can make them

de-bias themselves. A little, not much. On the other hand,

I think organizations, if they are very conscious

of what they want to accomplish, they, quite possibly,

can put in place procedures that will

protect them from different kinds of errors. We change the system

rather than our behavior. Yeah, like, I mean,

we've had these strategies for 35 million years. That is an evolutionary

enormous amount of time. We're not gonna just

kind of override them because in 2008,

we did some dumb things. Like, those things

are here to stay. We're gonna be

much better off if we change the system

around those biases. So, hey, we're not rational, but we can be smart enough

to set up the system to allow us to thrive even though we have

these biases that are

a little bit dumb. The real problem here is not the particular events that kicked off

the crash in 2008, the real problem is the way

the banking system is designed. There are two things,

really, about it. I mean, one is to understand the systemic nature

of financial instability. But the other part of it,

actually, is if you do understand the systemic nature

of instability, then, lots of other things

have to change. If you are determined to make sure that it--

it doesn't come back uh, you know,

within ten or 15 years and-- and bite you

in the backside again. We've come up,

as human beings, with the most fragile design

of financial system we could possibly think of. So, we need to re-think what we need

a financial system for, and then design one that will, uh, provide

those various functions. And that might mean

Translation

Translate and read this script in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this screenplay to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Boom Bust Boom" Scripts.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2025. Web. 23 Feb. 2025. <https://www.scripts.com/script/boom_bust_boom_4489>.

Discuss this script with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In