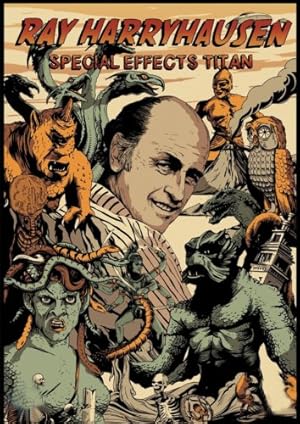

Ray Harryhausen: Special Effects Titan Page #9

(John Lasseter) All the guys at Aardman

doing clay animation.

I mean, come on!

Wallace & Gromit

in any other medium? No!

The storytelling that they do,

the subjects that they choose,

lend itself to the stop motion medium.

(Nick Park) You know, when you're sat

there with a character, it's in front of you,

you use your fingers,

you're holding it, you're handling it,

there's a kind of...

There is a kind of connection.

Unlike all the other types of animation,

what you see is a real performance.

and the animator

has to make that journey.

you'll do these key poses

and then a computer or an assistant

will in-between.

And you can manipulate those

and change.

To lock yourself away in a studio

and be able to move something

with hundreds of joints...

If you lose the thread,

the thing just becomes nonsense.

(Phil Tippett) Shots can sometimes take

up to 15 or 20 hours.

If there's a mistake,

if there's one mistake,

if the camera goes crazy

or your puppet breaks, you're doomed

and you have to

start the process all over again.

Occasionally, if the phone rings,

I answer it and that's maybe

where you'll see a little bit of a jerk

because I'd forgotten

whether one head was going forward

or one head was going backward.

Now, with digital and videotape,

the stop motion animators

have a way of keeping track.

Ray did it all in his head!

(Monkey chatters)

You animate the model

and one pose leads to another pose.

It is like sculpting, you have to know

what you're doing and then just do it,

because if you try to think about it,

It's not an intellectual thing,

it's an intuitive thing.

And I think that, for me,

is really important, to have that contact

and you're manipulating it

frame by frame

so you're kind of struggling with it.

Like in any kind of a live performance,

for some other adjustment

that you may wanna do.

You may be thinking that

you're gonna do this,

but you'll get into it

and all of a sudden you'll realise,

"You know what?

I could do this instead."

And so you can improvise.

(Ray) You may know the broad concept

of what's happening in the scene

but all the little details

are put in as you go along

by your imagination.

(Creature roars)

There was a man who said, "Why do you

go to the trouble of using stop motion?

"Why don't you put a man in a suit'?"

Well, that's the easy way out.

In the 15 features I've made

and the many shorts,

I did all the animation myself.

And I was able to do that

up until the '80s.

I was a loner.

I preferred to work by myself

because animation requires

an enormous amount of concentration.

In the days of Ray Harryhausen,

it was Ray

and a guy that used to click the shutter

on the camera.

And he'd do the thing and the guy would

click. And it was two guys doing it.

Now it's an army.

Today, of course,

it takes 80 people, 90 people.

You see them credited on the screen.

One person does the eye,

one person does the nose,

one person does the tail of the donkey.

One person's doing the facial,

another person's doing the body.

Sometimes another person can be doing

even tail motion or ear motion.

People doing the layout,

people doing the lighting.

You know, there's a whole team

that's a shader team.

I don't even know what they do!

It's a different atmosphere.

Some shots that are done today

with computer graphics

were the entire budget for their movies.

And so the economy of a singular guy

working on this thing,

it was very important that he was able

to have creative control over the stuff.

Now it's such a big organization

with many, many producers and

many effects technicians working on it,

it's difficult to give a singular vision.

There really aren't very many singular

vision films actually made any more,

unless you're a Spielberg or a Cameron

or a Peter Jackson,

a director strong enough to be able

to put that vision all the way through,

and even then,

it kind of needs to be watered down

cos there are so many people

working on it.

One person must arbitrate

between many, many good ideas.

You know, should it be lit like this

or should it be lit like that?

And they're all valid choices.

Should the creature be green

Or Should ii be brown?

Any choice you make is gonna be valid

when you're working

with such talented people.

But one person does have to arbitrate

and sometimes it's a very arbitrary choice.

That is defined by specific individuals,

by an author,

and in most cases, that's the director,

but with Ray Harryhausen,

it was the visual effects artist.

I'm grateful that I was able

to do what I did

without having any interference

from the studio or from anyone.

I remember somebody made a film

and they had just an actress

with a wig on with snakes.

Every time she walked, they would

bobble up and down, you know?

It wouldn't frighten a two-year-old child.

So I always wanted to animate Medusa

and I had a great chance

when Clash Of The 77?ans came about.

so that she wouldn't have clothes.

That's why I gave her a reptilian body,

because I didn't wanna animate

flowing cloth.

We gave her the arrow

from Diana's bow and arrow

and the rattlesnake's tail,

so she could be a menace

from the sound-effect point of view.

It became a big problem

because she had 12 snakes in her hair

and each snake had to be moved,

the head and the tail,

every frame of film,

along with her body and her face

and her eyes and the snake body.

The Medusa sequence,

if you see that film,

the tension that builds up between...

...the actor and his shield

and everything

that goes on there,

and you realise the bulk of it

is just stop motion,

close-ups of stop-motion.

It's a wonderful piece of work.

(Ray) I wanted green eyes for Medusa,

but I couldn't get them

so I had to use blue eyes,

unfortunately.

They were dolls' eyes, little

baby dolls' eyes that were put in her skull,

and you would roll them around

with the stop motion process.

I would move them

with an eraser of a pencil.

(Guillermo del Toro) People think

if you design monsters,

you design them for the sake

of making them cool,

but you never do that.

You design them to be

the character that you want them to be.

A good monster has to have character,

has to have a personality,

you know, it has to be

crazy, savage, funny.

Whatever you wanna use,

you have to define it by the silhouette,

the details, you know?

And if the monster works like that

then it's a well-designed monster.

(Ray) The monster that attacked

Andromeda in Greek mythology,

there are various concepts

of a dragon-like creature.

I wanted to make it semi-human so it

Translation

Translate and read this script in other languages:

Select another language:

- - Select -

- 简体中文 (Chinese - Simplified)

- 繁體中文 (Chinese - Traditional)

- Español (Spanish)

- Esperanto (Esperanto)

- 日本語 (Japanese)

- Português (Portuguese)

- Deutsch (German)

- العربية (Arabic)

- Français (French)

- Русский (Russian)

- ಕನ್ನಡ (Kannada)

- 한국어 (Korean)

- עברית (Hebrew)

- Gaeilge (Irish)

- Українська (Ukrainian)

- اردو (Urdu)

- Magyar (Hungarian)

- मानक हिन्दी (Hindi)

- Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Italiano (Italian)

- தமிழ் (Tamil)

- Türkçe (Turkish)

- తెలుగు (Telugu)

- ภาษาไทย (Thai)

- Tiếng Việt (Vietnamese)

- Čeština (Czech)

- Polski (Polish)

- Bahasa Indonesia (Indonesian)

- Românește (Romanian)

- Nederlands (Dutch)

- Ελληνικά (Greek)

- Latinum (Latin)

- Svenska (Swedish)

- Dansk (Danish)

- Suomi (Finnish)

- فارسی (Persian)

- ייִדיש (Yiddish)

- հայերեն (Armenian)

- Norsk (Norwegian)

- English (English)

Citation

Use the citation below to add this screenplay to your bibliography:

Style:MLAChicagoAPA

"Ray Harryhausen: Special Effects Titan" Scripts.com. STANDS4 LLC, 2024. Web. 23 Nov. 2024. <https://www.scripts.com/script/ray_harryhausen:_special_effects_titan_16619>.

Discuss this script with the community:

Report Comment

We're doing our best to make sure our content is useful, accurate and safe.

If by any chance you spot an inappropriate comment while navigating through our website please use this form to let us know, and we'll take care of it shortly.

Attachment

You need to be logged in to favorite.

Log In